Universal Design Versus Accessibility/Accommodation

With about one-quarter of Americans experiencing some type of disability, we must be thoughtful about inclusion in the workplace. This means considering accessibility and accommodations for existing worksites, but we are at a time when universal design should be the driving consideration. Universal design means considering access for all people from the moment we design a building, facility, transportation, write policies, or create software. If we design from the beginning to meet everyone’s needs, accessibility is no longer an issue.

Universal design ensures that environments are inherently accessible, reducing the need for adjustments or retrofitting later. It’s the ideal approach we should aim for, not just for ethical reasons, but because it makes good sense from a practical and economic standpoint. When we start with the concept of universal design, we create spaces and systems that work better for everyone, not just for a specific group. In this context, it’s important to rethink how we approach inclusion and consider making universal design a cornerstone of all our processes.

Medical Model and Accommodation

I became a certified vocational evaluation specialist in 1987. During those early years, vocational evaluators had significant responsibility in determining accommodation and accessibility opportunities for people with disabilities. This was before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and there were few legal requirements for employers to offer accommodations. While it was clear to many of us that creating access and offering accommodations were essential for placing people with disabilities in jobs, most employers were reluctant to consider accommodations. Many feared the cost or worried about setting a precedent for future situations.

This environment was marked by a pervasive belief in the medical model of disability. The medical model views the person with a disability as having a deficiency or limitation that needed to be fixed. The challenge was with the person…not the setting. Vocational rehabilitation counselors, case managers in supported employment, and vocational evaluators worked with a deficit-focused approach, looking for ways to overcome challenges that were seen as inherent to the individual. I, too, had yet to be exposed to the social model of disability, which would radically shift my perspective on how we view disability and inclusion.

Social Model of Disability

Early in my career as a professor, I was introduced to the social model of disability, and it completely changed my perspective. The social model, first proposed by Paul Hunt and Vic Finkelstein, fundamentally redefines how we understand disability. Rather than viewing disability as a problem within the individual, the social model recognizes that people are disabled by societal structures, attitudes, and environments. This model suggests that the barriers faced—whether they are physical, attitudinal, social, or even policy-based—are what causes disability, not the impairment itself. In this light, disability is not an inherent condition of the individual; it is a result of an environment that is not designed to accommodate everyone.

The social model led directly to the concept of universal design. Universal design advocates for creating environments, tools, and policies that meet the needs of all people from the start. If every building, piece of software, or transportation system is designed with access for everyone in mind, no individual will be excluded. This shifts the responsibility from the person with a disability to the world around them, encouraging a proactive, inclusive approach to design.

Universal Design v. Accessibility

The difference between creating accessibility or using accommodations and universal design is significant. Accessibility and accommodation are often reactive solutions, implemented after the fact to address specific needs or issues. These solutions are vital, but they often emerge from an environment that was not designed with inclusivity in mind from the outset. Universal design, in contrast, anticipates the needs of everyone and seeks to eliminate barriers before they arise.

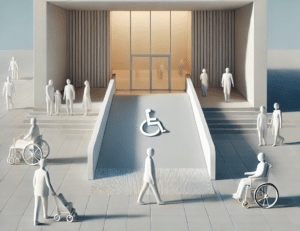

By integrating universal design principles from the beginning, we eliminate the need for retrofitting and ensure that the spaces we create work for all individuals. Universal design doesn’t just benefit people with disabilities; it creates environments that are better for everyone. For example, a ramp at a building entrance is helpful to people in wheelchairs, but it also benefits people with strollers, those with temporary injuries, and older adults. Similarly, accessible websites benefit not only people with visual impairments but also those who may need to adjust font sizes, those with cognitive challenges, and even those who prefer text-based navigation. The benefits of universal design extend far beyond any single group.

Universal design is the ideal solution for creating a truly inclusive society. If we design buildings, transportation systems, communication methods, and policies to meet the needs of everyone, accessibility and accommodation become unnecessary. This isn’t just a moral or ethical stance; it is a responsible position and makes economic sense. Creating inclusive environments from the start saves money in the long run, reduces the need for retrofitting, and opens opportunities for a wider range of people to fully participate in society. In the workplace, inclusive design means creating systems that allow all employees to contribute effectively, leading to a more productive and diverse workforce.

I had the privilege of visiting Microsoft’s facilities in 2005, where I saw firsthand how universal design principles could be implemented in the workplace. Microsoft had designed model homes and offices of the future, where physical and communication access were prioritized. These examples prove that universal design is not a far-off ideal but a viable and practical solution that can be implemented today. Such proactive approaches not only increase accessibility but also enhance the overall experience for everyone. Designing with inclusivity in mind improves the user experience and creates environments that are more adaptable to changing needs.

Role of Artificial Intelligence

As I prepared to write this blog, I also considered the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in universal design. AI has the potential to assist in addressing some access issues, particularly in software and communication. However, AI is not without its challenges. One of the biggest problems with AI is its reliance on algorithms that are designed to meet the needs of the majority. These algorithms often overlook the needs of individuals with unique or less common requirements, making AI an imperfect tool for universal design. One key proposal for addressing this issue is to ensure that human connections are involved in the decision-making process, particularly involving people with disabilities, vocational rehabilitation counselors, vocational evaluation specialists, and assistive technology specialists. While AI can be valuable in enhancing universal design, it cannot replace the need for human input and collaboration in the process.

Alliance and Universal Design

I have been fortunate to work with Alliance Enterprises because their company culture prioritized access for all in their software design from the very beginning. The company’s original owner took the initiative to sit down with a person who was blind and work through the software line by line to ensure its accessibility. This commitment to universal design has remained the company’s focus for nearly 25 years. I have also been involved in the design of Aware Express for CRP (case management software for community rehabilitation programs), where leadership ensured mobile-first, full access from the start. To achieve this, we partnered with the Helen Keller National Center (HKNC), where users worked closely with developers and testers to ensure full accessibility from the beginning. Alliance has become a leader in fully accessible case management software in vocational rehabilitation.

Conclusion

As we move forward, I strongly believe that embracing the Social Model of Disability is essential to fostering respect and opportunity for people with disabilities. Our society has the potential to be fully inclusive, but it requires us to design environments, systems, and policies that remove the barriers that currently exist. Focusing on universal design will resolve many of the issues that persist today. While accessibility and accommodation will continue to serve as necessary solutions in the short term, universal design should be our long-term goal.

(Final edits with assistance from ChatGPT)